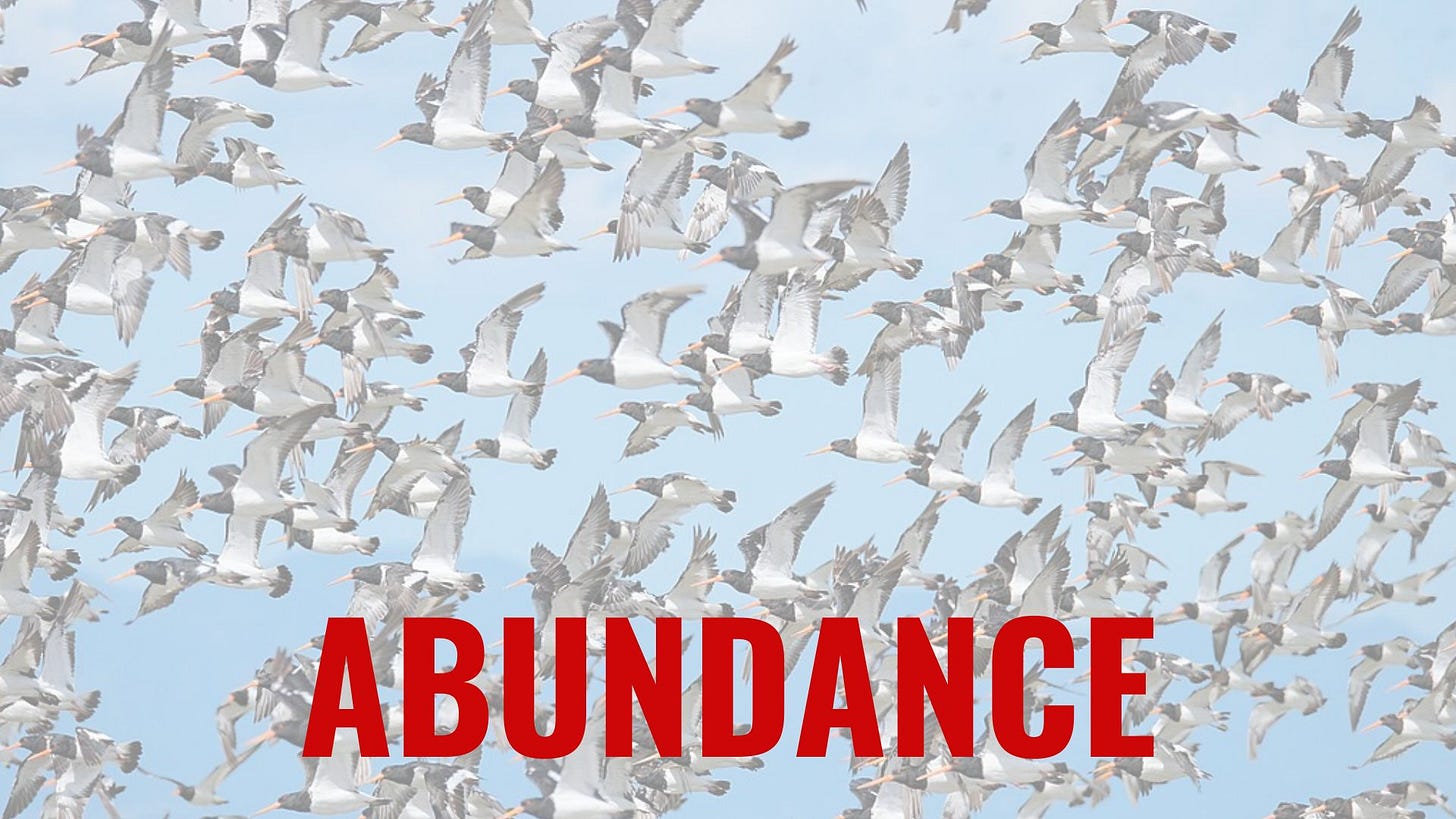

Words We Need: Abundance

Conservation is preoccupied with scarcity. Let's change that.

One thing I’ve learned from years of writing about conservation is that the English language doesn’t have enough words for it, and those that we do have can be counterproductive. “Words We Need” suggests some ways to fill the gap. Ideas welcome.

Last week, the members of Washington State’s Wolf Advisory Group held a public meeting in the small town of Colville, just a mile or so south of the Canadian border. The group, which is composed of ranchers, hunters, and conservation advocates, has been meeting regularly with state wildlife agency representatives for more than a decade. Considering the fierce differences among the members, that’s an accomplishment in itself.

During the Colville meeting, though, the group members’ carefully cultivated patience frayed. The ranchers were tired of losing lambs and calves to wolves, and the situation, they said, was only getting worse. (“I lost 17 percent of my calves last year. You take 17 percent of your income and set it on fire,” one group member told her colleagues.) Several years ago, the group developed a statewide protocol to reduce livestock losses — and compensate ranchers for losses that do occur — but ranchers said those measures were often rendered useless by bureaucratic delays. One rancher, describing the emotional toll of dead livestock and lost earnings, reminded the rest of the group that ranchers and farmers are more likely to die by suicide.

The argument was painful to watch, much less take part in, and while all the group members stayed in their seats until the meeting adjourned, ranchers, conservationists, and agency representatives expressed weariness and frustration. Some wondered aloud whether their conversations were still worthwhile.

From a distance, the return of wolves to Washington State is an astounding conservation success. When individual wolves began showing up here in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the species hadn’t been seen in the state since the 1930s; now, Washington is home to an estimated 260 wolves in 42 packs. Yet if the mood in Colville is any indication, this success is far from secure.

There are countless reasons for chronic conflicts between people and wolves (and between people over wolves) in Washington State and elsewhere. One of them is that conservation institutions — government agencies and NGOs alike — aren’t equipped for the problems of abundance.

Most conservationists are first responders: they’re dedicated to preventing species extinction. Continued existence of a species, even in tiny numbers, is celebrated — and given the multiplying obstacles to survival, it should be.

Sometimes, however, conservation efforts achieve much more. Gray wolf numbers are nowhere near what they once were, but wolves are recovering in both North America and Europe, and are now abundant enough to take up residence in places humans have long considered theirs.

As Jiajia Liu and colleagues write in a recent paper in Bioscience, this kind of significant, sustained recovery has inevitable consequences for both humans and host ecosystems. If conservationists don’t have the multidisciplinary research and other resources they need to address those consequences, the species is likely to be persecuted or confined to inadequate habitat or both. Even dramatic recoveries can easily be arrested or reversed.

For years now, the conservationists, ranchers, and hunters who make up the Wolf Advisory Group have willingly taken part in some very uncomfortable conversations. Despite their low spirits last week, they will surely continue to meet. But the problems they face are complex and stubborn, and not even the most dedicated group of frenemies can solve them alone. Lasting recovery requires conservation institutions to think beyond scarcity and prepare for what so often seems impossible: success.

Wishing an abundant Thanksgiving to all who celebrate. See you again soon.

I think Diane Boyd said it best: wildlife management is people management. However, we need to find a balance between healthy, thriving and growing wildlife populations (of species recovered from near-extinction and/or extirpation), and the needs of communities living in close proximity with large charismatic predators such as wolves and grizzlies. I doubt that ranchers will ever grow to love wolves in their midst, even if the impacts on livestock are minimal. The best remedy seems to be what American Prairie is doing with Wild Sky, and what the Northern Jaguar Reserve is doing with Viviendo con Felinos: namely incentivizing ranchers and landowners to encourage wildlife on their property. Compensation for livestock lost also goes a long way towards easing tension.

Most folks would agree that more wolves and grizzlies on the range is inherently good for the landscape, and that abundance within nature's own system of checks and balances will and should prevail. I guess we often do not know how to react to a good thing, or good news for that matter.

As always, another interesting, clear-headed and thought-provoking article from Conservation Works - always a delight to read.

The narrative of scarcity is pervasive in so many ways. "The market" creates scarcity because there's no profit in abundance. Must conservation adopt the same narrative? Thought-provoking, Michelle, thanks.